Feeding the Forgetting: The Nutritional Strategy for Cognitive Resilience

Feeding the Forgetting: The Nutritional Strategy for Cognitive Resilience

Imagine your mind as a vast, intricate library. In normal aging, finding a book might take a little longer. In Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), whole shelves begin to subtly shift—names evade you, appointments slip through the cracks, and the thread of complex tasks frays. MCI is not dementia, but it is the most significant clinical precursor to it. It represents that fragile, intermediary stage where cognitive decline is noticeable but doesn't yet disrupt independent daily life

For decades, this territory was viewed with a sense of inevitability. Today, a paradigm shift is underway, led by nutritional psychiatry and lifestyle medicine. We now understand that the brain is not a passive spectator to aging; it is a metabolically active organ deeply responsive to its environment—especially the nutrients it receives. This article explores MCI not as a point of no return, but as a critical intervention window. We will map the dietary and lifestyle pathways that can fortify cognitive resilience, support brain structure, and potentially alter the trajectory of memory itself

Understanding MCI – The Brain's Subtle SOS

MCI is characterized by a measurable decline in cognitive abilities—particularly memory, executive function, or language—that is greater than expected for age and education, yet not severe enough to constitute dementia

The Clinical Reality: An estimated 15-20% of adults over 65 have MCI. Each year, about 10-15% of those with MCI progress to Alzheimer's dementia, compared to 1-2% of the general older population

Two Primary Types: Amnestic MCI primarily affects memory. Non-amnestic MCI affects thinking skills like planning, judgment, or visual perception

A Window of Opportunity: This stage is now recognized as the optimal time for preventive intervention. The pathological processes (like amyloid plaque accumulation and neuroinflammation) are active, but the brain's plasticity and compensatory abilities remain largely intact, making it responsive to positive inputs

Understanding MCI – The Brain's Subtle SOS

MCI is characterized by a measurable decline in cognitive abilities—particularly memory, executive function, or language—that is greater than expected for age and education, yet not severe enough to constitute dementia

The Clinical Reality: An estimated 15-20% of adults over 65 have MCI. Each year, about 10-15% of those with MCI progress to Alzheimer's dementia, compared to 1-2% of the general older population

Two Primary Types: Amnestic MCI primarily affects memory. Non-amnestic MCI affects thinking skills like planning, judgment, or visual perception

A Window of Opportunity: This stage is now recognized as the optimal time for preventive intervention. The pathological processes (like amyloid plaque accumulation and neuroinflammation) are active, but the brain's plasticity and compensatory abilities remain largely intact, making it responsive to positive inputs

The Pillars of Neurodegeneration – What Nutrition Can Address

Cognitive decline is driven by interconnected biological processes that are directly modifiable by dietary patterns

Chronic Neuroinflammation: The brain's immune cells (microglia) can become persistently activated, releasing inflammatory cytokines that damage neurons. This "smoldering fire" is fueled by systemic inflammation, often originating from poor diet, obesity, and gut dysbiosis

Oxidative Stress: An imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants leads to cellular damage. The brain is especially vulnerable due to its high oxygen consumption and lipid-rich content

Vascular Dysfunction: Reduced blood flow to the brain, stemming from hypertension and atherosclerosis, deprives neurons of oxygen and nutrients. As the saying goes in neurology, "What's good for the heart is good for the brain

Impaired Glucose Metabolism: The brain's ability to use glucose for fuel can decline years before symptoms appear. Some researchers even call Alzheimer's "Type 3 Diabetes" due to this insulin resistance in the brain

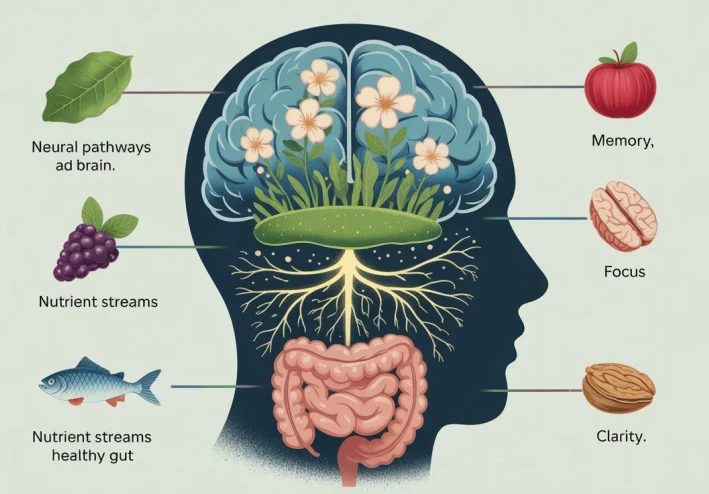

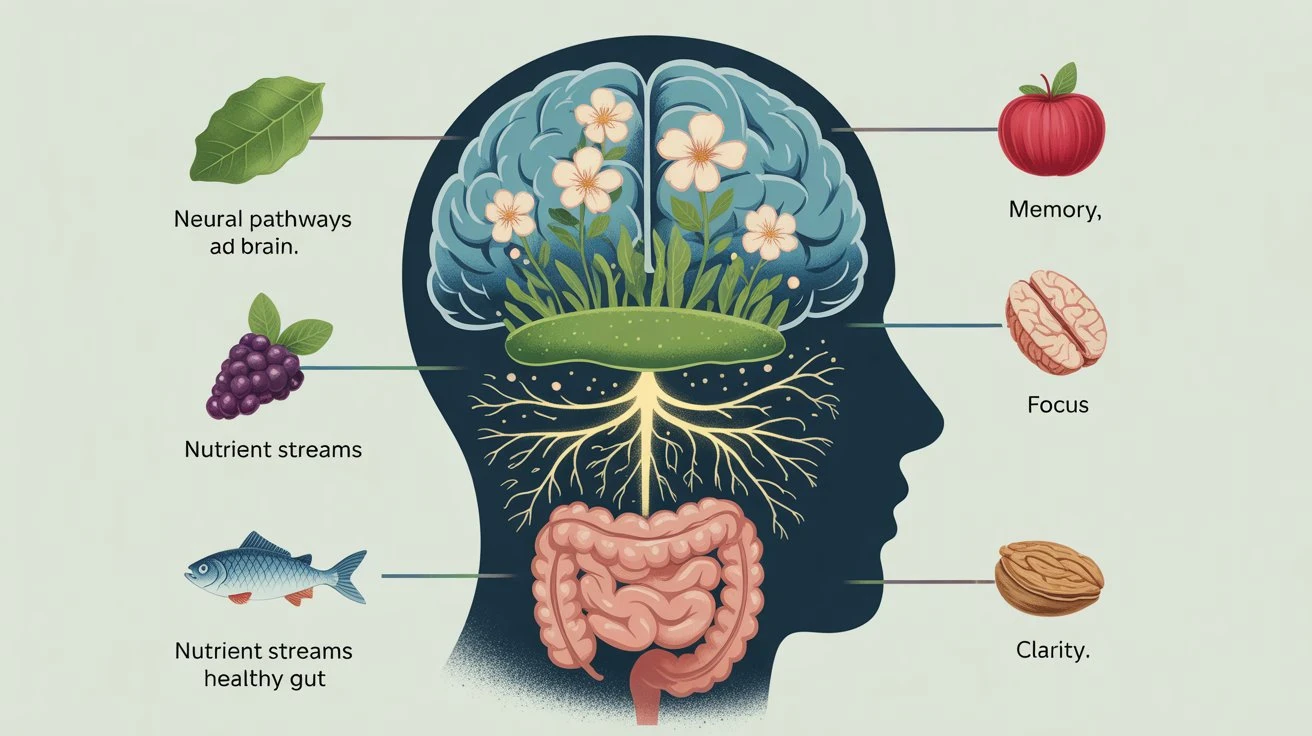

Gut-Brain Axis Disruption: An unhealthy gut microbiome can produce inflammatory molecules and amyloid proteins that may travel via neural and circulatory pathways to the brain, influencing neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration

The MIND Diet – A Blueprint for the Brain

The most compelling dietary evidence comes from the MIND diet (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay). It synergistically combines elements of the heart-healthy Mediterranean and DASH diets, specifically targeting brain health

The Core Commandments

Green Leafy Vegetables: (e.g., kale, spinach, collards): 6+ servings/week. Rich in brain-protective vitamins K, lutein, and folate

Other Vegetables: 1+ serving/day. A diversity of colors and types

Berries: 2+ servings/week. Especially blueberries and strawberries, packed with flavonoids that cross the blood-brain barrier to reduce oxidative stress and inflammation

Nuts: 5+ servings/week. For healthy fats, vitamin E, and antioxidants

Olive Oil as primary oil

Whole Grains: 3+ servings/day

Fish: 1+ serving/week. For omega-3 fatty acids (DHA), a critical structural component of brain cells

Poultry: 2+ servings/week

Beans: 4+ servings/week. For fiber and brain-healthy B vitamins

Wine: 1 glass/day (optional, with medical approval)

The Foods to Minimize: The MIND diet also emphasizes limiting

Red meat & processed meats

Butter and margarine

Cheese

Pastries and sweets

Fried or fast food

Landmark research from Rush University, published in Alzheimer's & Dementia, found that even moderate adherence to the MIND diet was associated with a 35% reduced risk of Alzheimer's, while strict adherence was associated with a 53% reduction

Beyond the Plate – The Integrated Cognitive Resilience Protocol

Nutrition is the cornerstone, but cognitive health is built through multiple, synergistic lifestyle pillars

Targeted Neuro-Nutrients

Omega-3 DHA: Found in fatty fish (salmon, mackerel, sardines) and algae. DHA is integral to neuronal membrane fluidity and reduces amyloid-beta plaque formation. Supplementation is often recommended for those who don't eat fish

Flavonoids: Abundant in berries, dark chocolate, citrus, and tea. They enhance blood flow to the brain and promote the production of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), a protein that supports neuron survival and growth

Vitamin E (from food): Nuts, seeds, and leafy greens provide a complex of tocopherols that protect brain lipids from oxidation

B Vitamins (B9, B12, B6): Critical for homocysteine metabolism; high homocysteine is a risk factor for cognitive decline and vascular dementia. Sources: leafy greens, legumes, eggs, poultry

The Gut-Brain Conversation

A high-fiber, polyphenol-rich diet (from the MIND diet) nourishes a diverse gut microbiome

Probiotic and prebiotic foods (yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, onions, garlic) can help produce short-chain fatty acids like butyrate, which have anti-inflammatory effects that may reach the brain

Movement as Cognitive Fertilizer

Aerobic exercise (150 mins/week of moderate intensity) is one of the most potent strategies. It increases BDNF, improves cerebral blood flow, and directly enhances the size of the hippocampus—the brain's memory center

Resistance training (2x/week) also shows strong cognitive benefits, likely through improving metabolic and vascular health

Sleep as a Cleansing Cycle

During deep sleep, the brain's glymphatic system activates, clearing away metabolic waste products, including amyloid-beta. Prioritizing 7-8 hours of quality sleep is non-negotiable for cognitive maintenance

The Mind is a Garden

Mild Cognitive Impairment can feel like the first chill of a long winter. But the science of therapeutic nutrition and lifestyle medicine reveals that we are not powerless against this change. The brain retains a lifelong, albeit use-it-or-lose-it, capacity for neuroplasticity and self-repair

By adopting the MIND diet as a culinary compass, we provide the raw materials for neuronal repair and inflammation control. By tending to our gut microbiome, we quiet a source of systemic unrest. Through exercise and sleep, we stimulate growth and perform essential maintenance

This is not about preventing aging, but about changing the experience of aging. It is about cultivating a brain environment that is resilient, well-nourished, and actively defended. We must shift from a fear of forgetting to the proactive practice of feeding our cognitive future. The mind, after all, is not just a machine—it is a living ecosystem, and we hold the tools to cultivate its flourishing

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: If I already have MCI, is it too late to change my diet

A1: It is absolutely not too late. The brain's plasticity persists. While diet may not reverse existing damage, strong evidence suggests it can slow further decline, improve cognitive function, and support overall brain health, potentially altering your long-term trajectory. The MCI stage is precisely when intervention is most crucial

Q2: Are there specific supplements I should take for MCI

A2: The primary focus should always be on a nutrient-dense diet. However, some supplements have evidence

* Omega-3 (DHA): Beneficial if fish intake is low

* Vitamin B12: Crucial for older adults, as absorption can decrease

* Vitamin D: Linked to cognitive health; many are deficient

* Important: Always consult with a doctor before starting supplements, especially if on medication. High-dose supplements can have risks and are not a substitute for food

Q3: How does the MIND diet differ from just eating “healthy”

A3: The MIND diet is strategically specific. It emphasizes particular brain-protective foods (berries, leafy greens, nuts) and sets quantitative, evidence-based goals (e.g., "6 servings of greens per week"). It also explicitly identifies and limits the foods most harmful to brain health (processed foods, fried foods, cheese, butter), providing a clearer, more actionable framework than general healthy eating advice

Q4: Does having the APOE-e4 gene (Alzheimer's risk gene) mean diet won't help

A4: On the contrary, it means diet may matter even more. While you cannot change your genes, you can influence their expression (epigenetics). Research indicates that individuals with the APOE-e4 allele may experience greater cognitive benefits from healthy lifestyle interventions than those without it. Your genetics load the gun, but lifestyle pulls the trigger

Q5: How long does it take to see cognitive benefits from dietary changes

A5: Some benefits, like improved energy and focus from stable blood sugar, can be felt in weeks. Measurable improvements in cognitive test scores or biomarkers from sustained dietary change are typically studied over periods of 6 months to 2 years. Consistency is key—this is a marathon, not a sprint, for brain health